|

font |

books |

links |

credits |

how-to |

transliterator |

| contents | origins | artifacts | language | usage | extinction | revival |

|---|

Features of Alibata (Usage Guide)

Click here for my non-scholarly conjectures about how to write in alibata.The Graphs

The script consists of three graphs which stand for vowels (or, according to some scholars, they represent glottal stops followed by vowels13), and fourteen graphs which represent syllables consisting of a consonant and the sound /a/.

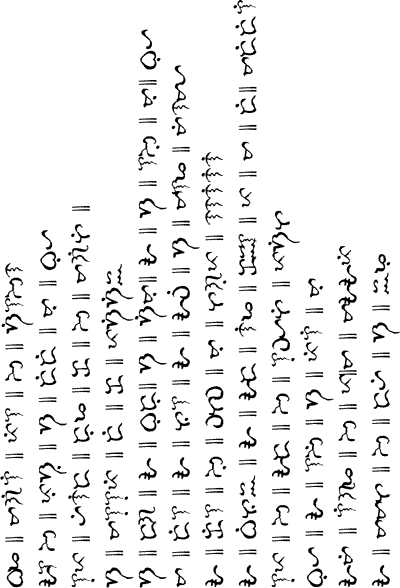

FIGURE 3

Alibata

Variant forms of writing

The Spanish recorded ten variations of Alibata, all of which were almost entirely identical except for minor details. 14 Many of these differences are due to the features of the languages they were used to record. For example, the Ilocano version of the script lacks wa and ha, while the Pampangan version lacks ya,wa, and ha.

Order of the graphs

Scholars typically present the order of the graphs as conforming

to the traditional order of other Indic scripts: a, e-i, o-u, ka,

ga, nga, ta, da, na, pa, ba, ma, ya, la, wa, sa, ha. However, the

Tagbunawa people have mnemonic rhymes which place the graphs in the

following order: o-u, a, e-i, la, ma, da, ga, ta, na, ha, ba, sa,

pa, ya, nga, wa. For example, one of the mnemonics is "U ai!

Lamang daga ta nakabasa pauyat wawa," which translates to an

insult and then the phrase, "If we cannot read, this is indeed

shameful, for it is merely a child's game."15 Almost every

segment of the rhyme is a value of one of the graphs. Still another

order is exhibited by "The A B C's in the Tagalog language," an

illustration of the Doctrina Christiana published in 1593 by Father

Doming de Nieva using type devised by the Chinese convert Keng

Yong. In this example, the graphs are ordered thus: a e-i o-u ha pa

ka sa la ta na ba ma ga da ya nga wa.16 The Spanish

eventually reordered the graphs to approximate the order of the

Roman alphabet: a, e-i, o-u, ba, ca, da, ga, ha, la, ma, na, nga,

pa, sa, ta, ya. The Spanish also

transliterated the graphs into Roman letters so that it adhered to

the conventions of written Spanish. For example ![]() was

transliterated as ga, and

was

transliterated as ga, and ![]() was transliterated as go-gu,

but

was transliterated as go-gu,

but ![]() was transliterated as gue-gui. Instead of ka, ke-ki, and

ko-ku, the Spanish transliterated

was transliterated as gue-gui. Instead of ka, ke-ki, and

ko-ku, the Spanish transliterated ![]()

![]()

![]() as ca,

que-qui, co-cu. 17

as ca,

que-qui, co-cu. 17

Direction of writing

The consensus is that the script was written in columns from the

bottom to the top, with each succeeding column written from left to

right.18 A

few Spanish missionaries claim the scripts were written in columns

from top to bottom, with each succeeding column written from left

to right. 19

Francisco Ignacio Alzina observed that people writing in the

Samar-Leyte region wrote in boustrophedon, except it was from the

bottom to the top for one column then from the top to the bottom

for the next column, and so on, alternating. 20 The orientation of

writing is depicted in Figure 3 below. Apparently, the text could

be read from the bottom to the top, or, after rotating the text

ninety degrees clockwise, it could also be read left to right, like

Roman letters. This is probably what the Spanish did, and this is

the reason that graphs are now represented from the left to right

instead of bottom to top.

FIGURE 4

Direction of writing

How to represent vowels

The vowel following the consonant can be modified by diacritical marks either above or below the graph. These marks are called kudlit. A kudlit placed above the graph changes the vowel to /e/ or /i/.

![]() ba

ba

![]() be-bi

be-bi

A kudlit below the letter changes the vowel to /o/ or /u/

![]() ba

ba

![]() bo-bu

bo-bu

In 1620, Father Francisco Lopez introduced the cross kudlit in order to represent certain Spanish words less ambiguously in his Ilocano version of the catechetical Doctrina Christiana. 21 The cross kudlit is placed underneath the graph and functions much as the virama in the scripts of India, so that the graph represents only a consonant.

![]() ba

ba

![]() b

b

Three, five, or six vowels?

The use of the three vowel graphs seems to be under contention. Some scholars assert that the languages actually possessed all five vowels, and all five were phonetically significant, but nevertheless /e/ and /i/ shared a graph, and /o/ and /u/ shared a graph.22 Others contend that all five sounds exist, but /e/ and /i/ are allophonic, as are /o/ and /u/, and the difference occurs depending on its position in the word, but generally these pairs of vowels are supposedly interchangeable. This idea is suggested by the Roman transliterations of certain words, which sometimes vary according to region. For exampleHow to write ra,re-ri, and ro-ru

In the earlier history of Alibata, ra, re-ri, and ro-ru were

represented as ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() (la, le-li, lo-lu.) But they

could also be represented as

(la, le-li, lo-lu.) But they

could also be represented as ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() (da, de-di, and do-du.) 24 The interchangeability of "l" and "d"

might be illustrated by the different words of different languages

for the word that means "day." In Cebuano and Ilocano, the word

used is aldaw. In Tagalog, the word is araw. But in

all cases, it would probably be rendered as

(da, de-di, and do-du.) 24 The interchangeability of "l" and "d"

might be illustrated by the different words of different languages

for the word that means "day." In Cebuano and Ilocano, the word

used is aldaw. In Tagalog, the word is araw. But in

all cases, it would probably be rendered as ![]()

![]()

![]() "a da u." In

some Philippine languages, /l/ and /r/ are truly allophonic, that

is, interchangeable. This is reflected in the fact that native

speakers of such languages confuse the two when trying to speak

languages where the two are distinct phonemes. In other Philippine

languages, such as Mangyan, which still uses a form of Alibata, /l/

and /r/ are written with the same graph, but they are distinct

phonemes. In still other Philippine languages, most notably

Tagalog, /d/ and /r/ are allophones. The following table

illustrates the cases in which /d/ is used, and the cases in which

/r/ is used.

"a da u." In

some Philippine languages, /l/ and /r/ are truly allophonic, that

is, interchangeable. This is reflected in the fact that native

speakers of such languages confuse the two when trying to speak

languages where the two are distinct phonemes. In other Philippine

languages, such as Mangyan, which still uses a form of Alibata, /l/

and /r/ are written with the same graph, but they are distinct

phonemes. In still other Philippine languages, most notably

Tagalog, /d/ and /r/ are allophones. The following table

illustrates the cases in which /d/ is used, and the cases in which

/r/ is used.

| Case | Word | Hypothetical rendering | Syllabification |

| /d/ occurring at the beginning of a syllable at the beginning of a word | daan "road, street, throughfare" |

da an (not ra an*) |

|

| /d/ occurring at the beginning of a syllable following a CVC syllable | dagdag "addition,extension" |

dag dag (not dag rag*) |

|

| /d/ found in the end of a syllable | tadtad "chopped into pieces" |

tad tad (not tar tar*) |

|

| /r/ occuring at the beginning of syllables in the middle of a word | nakaraan "bygone, past, former, departed" (derived from daan) |

na ka ra an (not na ka da an) |

The transformation of the /d/ to an /r/ is most apparent when changing an adjective into a verb. Normally in Tagalog, an adjective can be changed into a verb by adding the prefix "ma-." For example kita, which can mean "seen, can be seen, visible" can be transformed into makita, meaning "to be seen, to see." When this change is performed on an adjective that begins with a /d/, the /d/ becomes an /r/. For example dinig, which means "audible, can be heard." can be turned into marinig, which means "to hear, to be able to hear." As to the case where /r/ is the first letter of a word, this case was likely rarely if ever seen in pre-Hispanic Tagalog.

What to do with the final consonants of syllables

Like Linear B, the script used to render Mycenean Greek, the

Philippine scripts only indicate the onset, or beginning, of

syllables and do not display the coda, or the end, of a

syllable.25

Only CV syllables can be properly represented. The word

maganda, meaning "beautiful," would be rendered as ![]()

![]()

![]() (ma ga

da). The word sinta, meaning "love between man and woman,"

would be rendered as

(ma ga

da). The word sinta, meaning "love between man and woman,"

would be rendered as ![]()

![]() (si ta).

(si ta).

The convention is unclear about the final w of a syllable. In

Tagbanuwa, it would be represented as a "u" but in Mangyan, it is

not written. Thus, it is not certain whether Tagalog giliw

(meaning "darling, a person much loved") would be rendered as

![]()

![]() or as

or as ![]()

![]()

![]()

Not all codas are necessarily dropped when rendering

speech in Philippine script. Some words such as

masdan,(meaning "to look at or observe carefully")

palabsin,(meaning "to let out, to put out") and

tingnan,(meaning "to look at, to see") are actually

contractions of masidan, palabasin, and

tinginan, respectively,26 so that they could be represented as

![]()

![]()

![]() (ma si da) instead of

(ma si da) instead of ![]()

![]() (ma da),

(ma da), ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() (pa la ba si) instead of

(pa la ba si) instead of ![]()

![]()

![]() (pa la si), and

(pa la si), and ![]()

![]()

![]() (ti ngi na) instead of

(ti ngi na) instead of ![]()

![]() (ti

na).

(ti

na).

While the script cannot completely represent the

Philippine languages, it is not an unsurmountable difficulty when

reading it. As mentioned, the writing system of Linear B had the

same problem when writing Mycenean Greek. A similar situation

occurs in ancient Hebrew, which does not have symbols for vowels.

The occurence of vowels were determined by context and through

conventional usage. Also similar is the occurrence of homonyms in

English, in which the meaning of a word such as "bear" which can

either be an animal, or mean "to carry," must be determined through

context. Hence, it is likely that an ancient user of Alibata could

tell the difference between the love between a man and a woman

(Tagalog sinta) and a type of string bean (Tagalog

sitaw), both which could be rendered as ![]()

![]()

The incompleteness of the Philippine scripts are often attributed to the theory that these scripts were relatively new developments in the Philippine cultures, so that they did not have time to evolve more conventions to deal with the deficiencies. The coming of Arab culture and Islam through trade around the 9th century AD probably hampered this evolution and European colonization beginning in the 16th century completely disrupted this evolution. Moreover, since these scripts, in the strictest sense, were not an indigenous development, they were not particularly suited to represent Philippine languages.

Click here for my non-scholarly conjectures about how to write in alibata.

[ Documents and Artifacts which use Alibata ] [ Languages rendered by Alibata ]

[ Features (Usage guide) ] [ Reasons for extinction ]

[ Attempts to revive and reform the writing system ]

14Diringer, David. The Alphabet: A Key to the History of Mankind. (New York: 1948) 434.

15Francisco, Juan R. Philippine Palaeography. (Quezon City: Linguistic Society of the Philippines, 1973) 28.

16Scott 53

17Chirino qtd. from Barrows, David P. History of the Philippines. (New York:World Book, 1924) 69-71.

18Francisco 17-8

19Francisco 16

20Francisco 16

21Scott 57

22Diringer 435

23Francisco 49

24Francisco 44

25Francisco 45

26Rizal qtd. from Resurreccion,Celedonio O. "Rizal, Father of Modern Tagalog Orthography." Facts and issues on the Pilipino Language. Ed. Apolinar B. Parale. (Manila:Royal Publishing House, 1969) 177.